Aside from a horrendous Devendra warble tacked onto an otherwise serviceable take of "Katie Cruel" and a song that messes with Texas (sounding suspicously like Dire Straits, though no doubt Knopfler is a Jansch idolator), Bert Jansch's The Black Swan is one of the finest full-lengths of his esteemed career, behind Jack Orion, LA Turnaround, and maybe two or three more. Of course, the press all went to kneel'n'bob before the other fogies, Neil and Bob, to where I almost got a bloody forehead pounding aginst the wall at one national magazine that just wouldn't let me do a feature on the legend, opting instead to run a 2,000 word "meditation" (read: masturbation) on "Sweet Child O'Mine" that makes Klosterman look like a visionary in comparison. In a way, I'm just grateful to see the man when he recently came over to play some shows stateside.

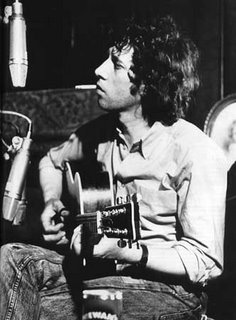

He was listening to jazz, country blues, modern blues and everything else. There were lots of people working in one area or another but nobody before Bert was actually putting them all together and blending them in that way...he just appeared fully formed.I forget just where the concept of folk as collage music, parallel to the DJ, comes from (Christgau maybe, or a Dylanologist like Greil?), but finally witnessing Jansch play live at the Southpaw, his first show in New York in nigh on a decade, it becomes evident during his set. Not that he makes his acoustic guitar go scratchy-scratch like Tom Morello or anything gimmicky like that, but just how he elucidates synapses between genres and disparate folks, tying them all together across time, reveals such craft. His own style stems from Big Bill Broonzy and Davy Graham and before most numbers, he tells of how he came to embody a song and the person behind it, who taught him the chords, the words. Opener Alan Licht does a bit of a mash-up as well, coupling the most heinous version of Richard Thompson's "Calvary Cross" (when he sings) with one of the most vicious (when he plays the song's guitar solo with a screwdriver).

In the same way that, say, The Game, understands the continuum of his music and shouts-out those who went before him, Jansch spends a good deal of the evening with yarns of Jackson C. Frank, Anne Briggs, John Renbourn, and Incredible String Band. He covers Frank's "Blues Run the Game" and "Carnival," delivers a stunning version of a tune he learned from Anne Briggs, "Blackwater Side," a folk ballad that depicts a one-night stand, with Jansch adding the note that "It's meant to be sung by a woman." The most deceptive thing about Bert Jansch is how he tucks his caliber of guitar playing inside the songs. Yes, he's the "Hendrix of the Acoustic," as Neil Young said, as Jimmy Page verified by basing III and Zoso's folk weirdness on the man, yet it's always inside the song itself, never extraneous. I'd be hard-pressed to point to a killer guitar solo or a flashy run by Bert Jansch. As Colin Harper noted in Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival: "(There's) a transcendant quality to the work implying that, at its heart, the work itself is the foreground and the creator a barely visible presence facilitating the construction of something magical."

Yes, it is a magical performance. Most surprising is when he tells a tale about his rendering of "Katie Cruel." It's a traditional standard that has been covered by the likes of Pete Seeger, not to mention an old bluegrass group of Jerry Garcia's, pre-Warlocks, pre-Dead. That he learned it from Beth Orton is a minor revelation, as it means his interpretation also stems from what is easily the definitive version of "Katie Cruel," Karen Dalton's kerosene-cured take on In My Own Time from 1971 (thankfully back in existence this year). It dashes my presumptive review in Paste Magazine wherein I figured he was just humoring the young'uns. Curious as to how such a song, existing across the strata of centuries, is so wholly embodied by a performer so as to be indistinguishable from it. How is Karen, not just from this late date, but at the exact moment that she first plucked it, not this Katie? Isn't "Katie’s Been Gone" from The Basement Tapes also about her? Don't they evoke her by her rightful name?

Not surprising though, as a similar thing occurred with folksinger Anne Briggs. For many ears, and generations of singers, Anne's takes of "Blackwater Side" and "Reynardine" are definitive, the others irretrievably indebted to her own stark takes. Which leads me to my other reason for being here in attendance on this night, which is to hopefully talk to Bert Jansch about his old running mate. It was he that helped craft Briggs's version of "Blackwater Side," and as I'm in the mi(d)st of a project involving her, his memories are crucial to my understanding of her. Ever since she scrapped a recording session in 1973, Anne Briggs has gone missing into the ether. I've searched in vain for the only article on her in recent memory, tracking her to a wee island in Scotland, in a piece that ran in MOJO, but its almost impossible to track. (Okay, I also don't want to pay $15 shipping for a copy from the UK.)

Weirder still is Anne Briggs's sudden appearance on some idyllictronica record from 2004. And even though it's only from two years back, that too is proving impossible to find. It's not even on Bit Torrent. To think that the even as the present quickens, it also hastens the recently-passed to disappear that much faster is a phenomenon seldom considered in the process of more and more consumption of music. Memory fades much like the woman herself, that spectral presence behind some of Jansch's most crucial works ("Wishing Well," "Go Your Way My Love"), that haunting voice resounding through the moors remains untenable, evoked only in the present, on a night when any moment in time can once again be picked out on a guitar. So when Mr. Jansch declines to speak with me on her, a most disheartening decision that leaves me clutching at the mysterious air surrounding her once more, even that feels strangely appropriate.