It requires two eyefuls to fully absorb the pandemonic Joe Coleman show at the Tilton Gallery, not to mention two rides above 14th Street to the UES (yes, I got nosebleeds from such heights), two hours to try and process the info crammed inside each small panel of acrylic pain(t). I may be the only person in the gallery without the two marks that denote most of Coleman's audience, tattoos or piercings. Although, when I arrive at the gallery for the second time, I see the man himself standing outside. He eyes my tee shirt with its image of Kali the Destroyer and approves.

It requires two eyefuls to fully absorb the pandemonic Joe Coleman show at the Tilton Gallery, not to mention two rides above 14th Street to the UES (yes, I got nosebleeds from such heights), two hours to try and process the info crammed inside each small panel of acrylic pain(t). I may be the only person in the gallery without the two marks that denote most of Coleman's audience, tattoos or piercings. Although, when I arrive at the gallery for the second time, I see the man himself standing outside. He eyes my tee shirt with its image of Kali the Destroyer and approves.How to attempt words that will properly convey the overwhelming sensations of his work? Familiar with artbooks that attempt to capture the madness coursing through each panel, seeing Coleman's collection up close (and I do mean up close, the eyes mere inches from the wall) is crucial to grasping his demons, his inspirations. As dense and prodigal as Bosch's visions, as brilliant as any illuminated manuscript, Coleman erects his own pantheon of gods through this portraiture. They serve as both biography and shrine, these devil-detailed studies of the most hallowed of sick-fucks: Henry Darger, Carlo Gesualdo, Hank Williams Sr., George Grosz, John Brown, Ed Gein, Hasil Adkins.

More like paintings to be appreciated by the four horsemen rather than mere humans, each slate gushes information and noise like an aneurysm in the brain of a schizophrenic. Writing and musical bars enframe each picture, some set against scraps of cloth (an American flag for John Brown, some girlie fabric for Darger). One work, reflecting on the Atomic Bomb like Gertrude Stein, invokes renderings of readiation sickness and mushroom clouds and surrounds them with swirling quotes and images: the Bhagavad-Gita, Boris Badanov, Timothy McVeigh, Alfred Nobel, and the lyrics of "Secret Agent Man" all conspire in Coleman's post-apocalyptic world.

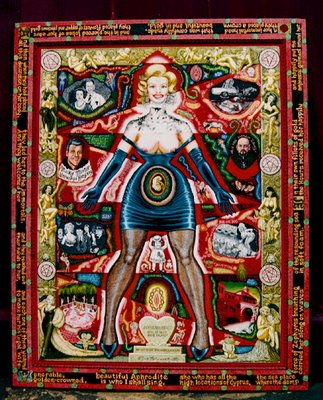

Joe's invocation of Jayne Mansfield is framed in angelic revelations and stanzas about Venus appearing on sea foam, her cunt surrounded with a crown of thorns. Coleman seeks to return her to a virginal state even as he surrounds her with soundbites from her b-movies as well as pentagrams and Anton LaVey (she was a high priestess in his Church of Satan), reveling in her sumptuous proportions while also showing her decapitated body already in decay. His other major subject is himself, turning his own story into mythology, much as his favorite subjects already have. Crafted with jeweller's loupe and one-bristle acrylic brushstrokes, Coleman accepts the fate of his faltering flesh and its precarious health; he both renders and rends him and his wife in more recent works, suggesting himself to be Vulcan to her Venus. He accepts the imminent decay of the body while also elevating it into that realm of demi-gods.