Fitting that my paperback copy of Kenneth Patchen's 1941 anti-novel The Journal of Albion Moonlight decides to give up the ghost as I read it, the glue of the spine loosing each page so that it'll be impossible to put back together again. And yet to try and hold on, to cling to characters, to plot, to keep it all together, is something Patchen realizes is a foolish endeavour within the narrative anyhow, so he prob'ly laughs down from heaven to see my copy fall apart, along with that other pain-wracked saint that sang about moonlight: "If you try to take it home, your hands will turn to butter."

Fitting that my paperback copy of Kenneth Patchen's 1941 anti-novel The Journal of Albion Moonlight decides to give up the ghost as I read it, the glue of the spine loosing each page so that it'll be impossible to put back together again. And yet to try and hold on, to cling to characters, to plot, to keep it all together, is something Patchen realizes is a foolish endeavour within the narrative anyhow, so he prob'ly laughs down from heaven to see my copy fall apart, along with that other pain-wracked saint that sang about moonlight: "If you try to take it home, your hands will turn to butter."Moonlight not only anticipates America's own plunge into the blood and madness of the Second World War (Hitler and Christ hang out with Albion's posse, though their inability to communicate is a sore point among the group), while also anticipating the Beats and the American counterculture. It illuminates a path later trod by others to greater, lasting fanfare: the atrocity exhibitions of Burrough's Naked Lunch, Ginsburg's glimpsing of those generational minds destroyed by madness, the ludicrous parades of deformed humanity glimpsed by pre-accident Bob Dylan. That overwhelming, helpless, maddening deluge drowns every word here, daring you to forget while also making true capture impossible.

"Patchen uses the language of revolt. There is no other language left to use," sez a like-minded figher, Henry Miller, in his essay on the poet, painter, writer. "One is no longer looking at a dead, printed book but at something alive and breathing, something which looks back at you with equal astonishment." Or if you care not a whit for criticism, just open the book itself. Or rather, shut it: "Close the covers of this book and it will go on talking. Nothing can stop it. Not life." Thus spake Moonlight.

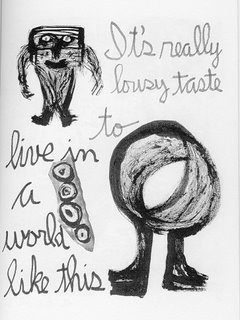

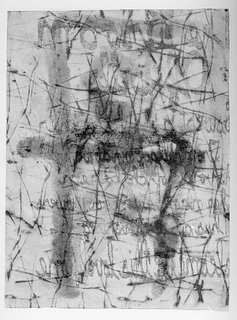

I'll admit that I don't know what to say about the text itself. It fragments, dissolves, willfully befuddles and contradicts, kills its characters to resurrect them in the next paragraph, so as to thrill with blowing them apart again. People within become chunks of charred meat: bewildering, horrific. Patchen is watching the propaghanda of the newsreels, yet seeing beyond, to the bayonets grown rusty from blood. How can he remain oblivious to it? And he fights the only way he can: hijacking popular styles for his own ends. Comedic slapstick, dime store pulp, ecclisiastic visions, fever dreams, surrealist spills, he vomits every ingested scrap back onto the page. Reading it at night makes my eyes delirious ("Fright causes the eye to see itself. There are words in our heads whose beauty is beyond our understanding"), lost in the disorder and rank mess of each page. How can the paper hold the melee of the battlefield along with the daily commute?

I'll admit that I don't know what to say about the text itself. It fragments, dissolves, willfully befuddles and contradicts, kills its characters to resurrect them in the next paragraph, so as to thrill with blowing them apart again. People within become chunks of charred meat: bewildering, horrific. Patchen is watching the propaghanda of the newsreels, yet seeing beyond, to the bayonets grown rusty from blood. How can he remain oblivious to it? And he fights the only way he can: hijacking popular styles for his own ends. Comedic slapstick, dime store pulp, ecclisiastic visions, fever dreams, surrealist spills, he vomits every ingested scrap back onto the page. Reading it at night makes my eyes delirious ("Fright causes the eye to see itself. There are words in our heads whose beauty is beyond our understanding"), lost in the disorder and rank mess of each page. How can the paper hold the melee of the battlefield along with the daily commute?"You will be told that what I write is confused, without order -- and I tell you that my book is not concerned with the problems of art, but with the problems of this world." Patchen is long-lost, most of his work out of print, rarely on shelves. The hallowed names in high school remain Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Salinger, anon, but even as I fear Patchen's obsolescence, his plunging down the memory hole for good, he lurches forth again like a zombie, like some horror that refuses to remain dead. Page 205, if I can find it in the heap of tenuous leafs, proclaims that "when the paint wears thin on the mask, they just haul out a new set of labels and begin all over again; they say 'Horror of horrors, what is this ghastly thing? Look what it says there! Fascism. Now isnt that barbarous! Surely you'll fight against that! The world must be saved from Fascism.'" Or Communism. Or this century's new shiny word.

It's then I realize that the struggles of this world have yet to expire. There's always a blank to fill in. The fight is ongoing: "When men are at war, there is no hatred of soldiers; it is the artist who is despised and reviled -- the only enemy of their fraud -- in truth, the one, real warrior."