Beta Blog celebrates Jandek's 47th record release.

Beta Blog celebrates Jandek's 47th record release.When I lived in Austin, there were no markers to memorialize --much less indicate-- that infamous act of public mass murder commited by Charles Whitman on August 1, 1966, when he shot nearly fifty people, killing 15 of them. An expert marksman, Whitman played Trophy Hunter with the student body: some were shot through the mouth, others through plate glass, between pick-up trucks, or while walking out of class or a store. A pregnant woman was shot through the abdomen, killing her unborn child. Students coming across the freshly killed thought they were witnessing guerilla theatre or some sort of psychology experiment until they too were absorbed into the terror of the reality.

I attended the University of Texas at Austin some thirty years on and knew fuck-all about that day. Sure, there remained holes in the buildings' limestone from rifle shots that had never been plastered over in the resulting decades and the tower itself still bears nodes from where good ol' boys lugged out their pistols and hunting irons to fire back. Unspoken so as to be forgot, silent so as to soothe that disquieting sound that is the echoing crack of a deer rifle's thunder, all but one trace of the man remained: it loomed over the entire landscape, glowed in the darkness of every night, both seen and unseen.

It's only in reading the oral history that comprises the newest issue of Texas Monthly that the day comes back into the light. Having come of age so as to be within the state lines during such atrocities as the Branch-Davidian Compound killings, the Luby's Massacre in Killeen, Texas, such public mass murder (to say nothing of the words "going postal" entering the vernacular) shockingly enough seemed normal in that state. Despite being knee-deep in the bloody mud of Viet Nam, the quaint smalltownness of Austin that is evoked herein is almost unimaginable. It tells of a time before EMS, before SWAT teams (the transportation of the dead was still handled by funeral parlors; tactical police teams were basically invented in the aftermath of Whitman). The Mayberry-ness of the Drag's storefronts (which border the west end of the campus) at that time and are fondly recalled here are as dead as the boho one captured thirty years on by Richard Linklater in Slacker. Both of these previous realities are now polished smooth by the Urban Outfitters and Barnes & Nobles.

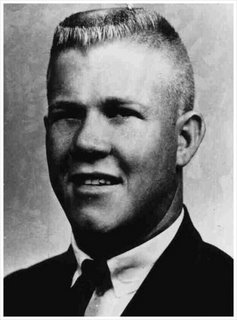

"Whitman was blond, good-looking, solidly built. I remember he seemed like a nice, clean-cut, all-American kind of guy," one recounts. Which is shorthand for saying he was a jock-asshole, but one of the thousands that still populate the university. The legend goes that an undiagnosed brain tumor waas the what made him ascend those stairs, though its more plausiable his amphetamine intake had more than a little to do with it. But what makes an All-American man see the world in a new, disturbing, isolated manner? What makes him create his own harrowing universe where he is the only inhabitant, the only assailant, the lone gunman?

Portrait of Whitman as a Young Man.

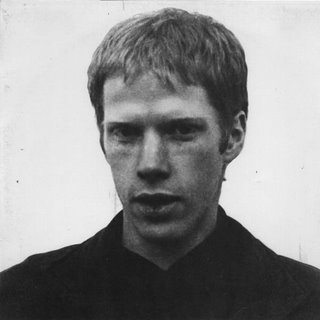

Portrait of Whitman as a Young Man.Seven years previous to the exact month, Texas Monthly ran an article about that enigmatic figure who still haunts the subconscious of Texas music, Jandek. Read about his legend elsewhere, or else watch Jandek on Corwood, but know this: music is not public, but extremely private; it grows and festers inside your skull. At that time, it was a shock to the esoteric music community of Texas that some blonde chick, as oppposed to some bespectacled cllector scum, had tracked him down and (gulp) had a beer with him. He lives as an anonymous normal businessman in Houston: black tie, black suit, with no explanation for the madness of the music that results, save that it's kin to growing snap peas. It made Charalambides' Christina Carter weep.

In much the same way that the ghost-white cassettes of Daniel Johnston floated at the periphery of the memory of Austinites, revealing to those with ears this devastating world that almost anyone could fall into if they but stepped towards the monolith, it was the same for Houston's denizens. One musician friend recalls flipping through record after record of this shirtless, bony man, seeing this parallel world evoked in blurry Kodachrome of pork-chop portraiture, backyards, wood-plank houses, cheap crepuscular drum kits, yet always flipping past them. And as Dante has Beatrice and Johnston has Laurie, Jandek has Nancy.

It would be tidy to suggest that in the forty years since the Whitman shootings there, have been forty Jandek records, except that with the release of Glasgow Monday/ The Cell, Janky's now on his 47th, a double disc of piano and whispers, contrabass and tuned toms. Perhaps he aims instead to make as many records as there were bullets that day?

He was one of those guys who got red-faced when he was upset, and he was very flushed when he walked in the door. He was carrying an architectural drawing that I suppose he wanted to show me, but the moment he saw that I had a baby grand in my living room, he dropped his papers, sat down, and played “Claire de Lune.” It’s a fairly tough little tune to play, but he did it beautifully. Then he played something else, though I don’t remember what. When all that red had drained out of his face, he stood up. I said, “Well, I’ll see you in class tomorrow, Charlie.” He said, “Okay,” and left.Reading the Whitman article by day, I screen the DVD release of Glasgow Sunday, his live public debut, in the night. The thought that there would ever come to pass a time when there would be a concert video of Jandek seemed as likely as meeting your own skeleton. Never shall that twain meet. And yet, that skeleton stands before us now, a face to our own mortality. Its bones clang, both heard and seen. The warm flesh that is music is riddled now with worms, hanging from those arms.

In early September of 1961 he was standing on the seventh-floor balcony of the Goodall Wooten dorm, looking at the Tower, when he turned to a friend and said, “You know, that would be a great place to go up with a rifle and shoot people. You could hold off an army for as long as you wanted.” He wasn’t like you or me; instead of seeing the Tower, he saw a fortress. Instead of rain spouts, he saw gun turrets.Finally witnessing this wraith-like figure, so unknowable yet familiar after decades of seeing his face on records that accrue and read like so many "Missing" bulletins on a curdled milk carton, like an innocent time killed on scalding hot pavement, he appears ancient, ageless. When he strums that first black note here, making adepts like Richard Youngs and Alex Neilson scurry to keep up with him, Jandek is resurrected as the last of the Texas bluesmen (or at least the dessicated corpse of Stevie Ray Vaughn). His tuning untempered, sensical and orderly only in his mind, the arrythmic tick of his heart untappable by others, his band scrambles to tie the skeleton back together. If Mance Lipscomb or Lightnin' Hopkins had played after their skin fell off the bone, it would've sounded as prophetic as Six and Six. The difference being that when Jandek saw a guitar, he saw not an instrument to affirm life (and the blues do embrace and celebrate this earth), but something that instead resounds with encroaching death, an instrument that is a wooden box, as hollow as its occupant.